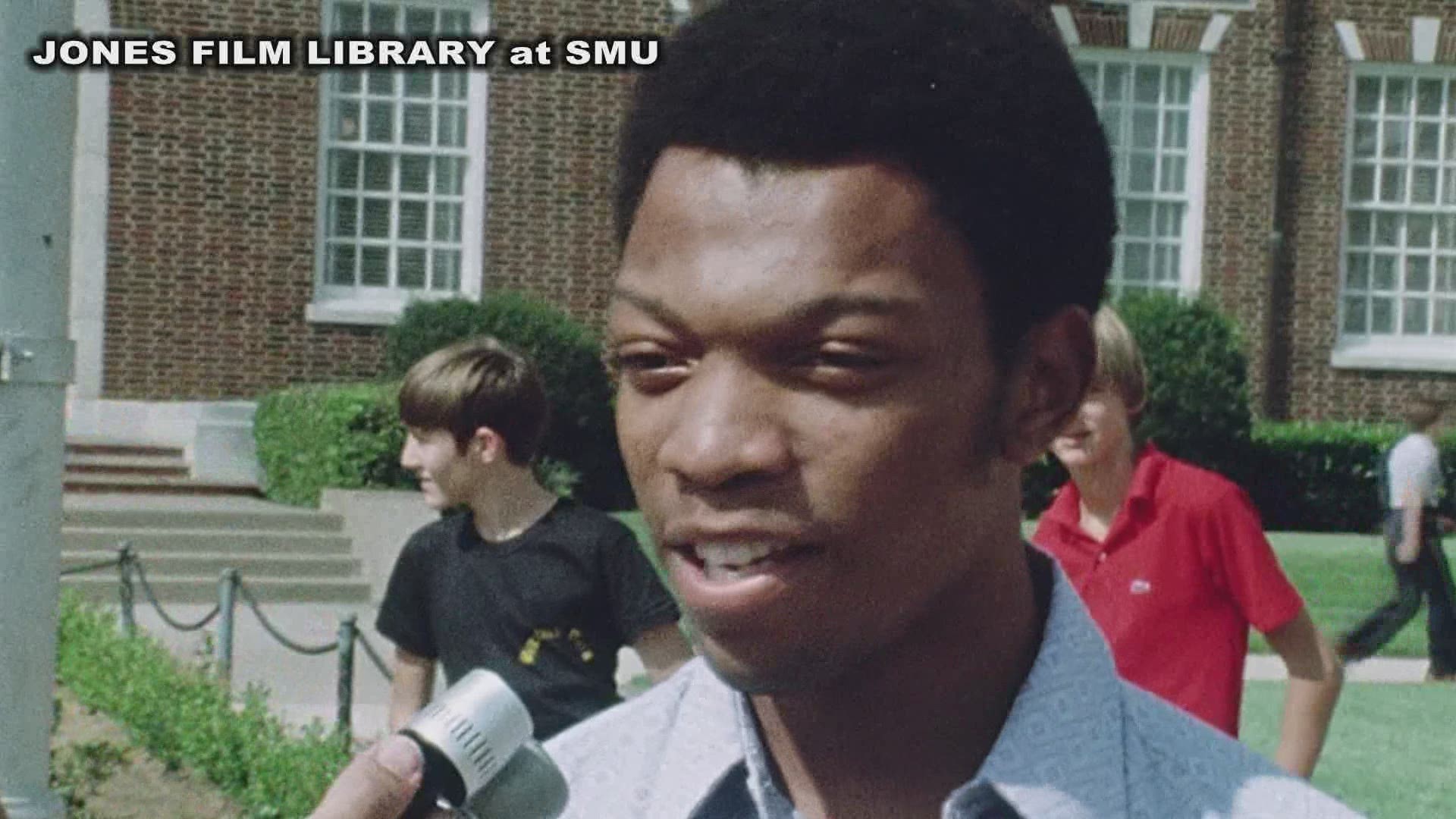

Bessie Coleman broke boundaries like very few that came before her. From learning another language to traveling around the world, the woman later known as "Queen Bess" became the first Black woman to hold a pilot license and influenced generations of Black pilots to follow in her footsteps.

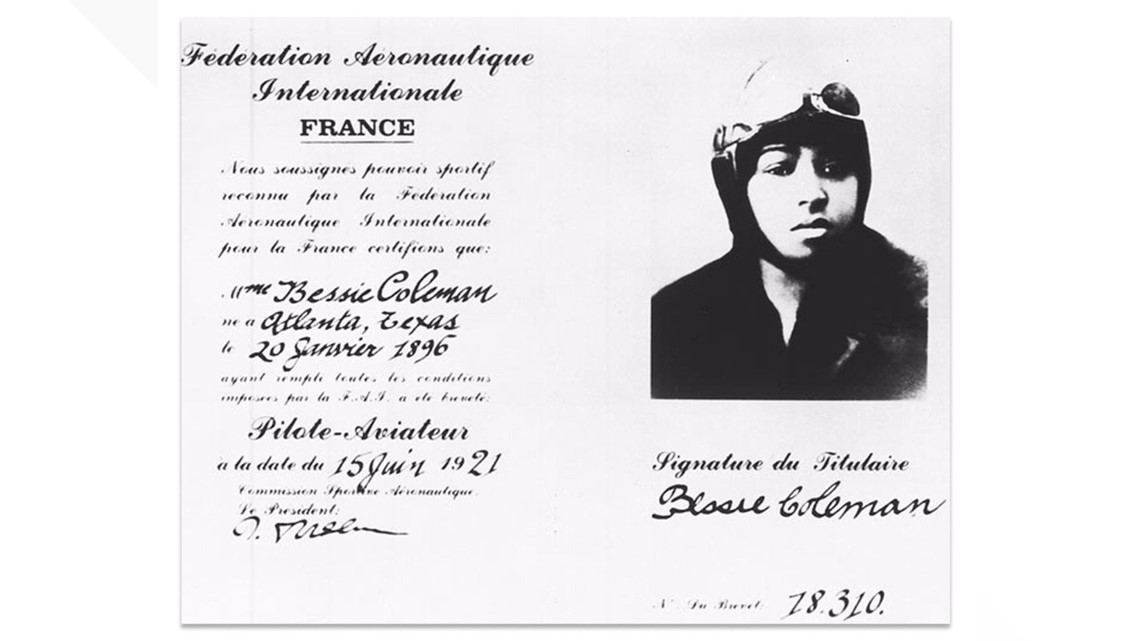

Coleman was born in 1892 in Atlanta, Texas, which is near where the Texas, Arkansas and Louisiana borders meet. She had 12 brothers and sisters.

Her father, George Coleman, was a sharecropper. His ancestors were both Native American and African American. Her mother, Susan Coleman, was an African American and worked as a maid.

The Coleman family moved to Waxahachie when Bessie Coleman was two, where they lived as sharecroppers.

Seven years later, when Bessie Coleman was nine, George Coleman moved back to Oklahoma in an attempt to escape discrimination. Susan Coleman and the rest of her family, including Bessie Coleman, remained in Waxahachie.

While going through school, Bessie Coleman earned money for herself by picking cotton and washing laundry.

In 1910, Coleman used her earnings to attend the Colored Agricultural and Normal University in Langston, Oklahoma, which is now known as Langston University. She returned to Texas after one semester because she ran out of money.

By 1915, Coleman decided to move to Chicago, where she initially lived with two of her brothers who were there at the time.

Coleman started out by going to beauty school and working as a manicurist at the White Sox Barber Shop. Many believe it is here she heard stories from pilots who would talk about flying during World War I. Some also say she started reading about aviation and watched videos of flights.

One of her brothers she was living with teased her because he said French women were allowed to learn how to fly airplanes and she couldn't in America, according to the National Women's History Museum.

At the time, American flight schools didn't admit women nor Black people. Robert S. Abbott, founder of the Chicago Defender, wrote about Coleman's quest in his newspaper. He also supported her financially along with Black bank owner Jesse Binga.

Abbott encouraged Coleman to move to France, which had some of the most racially-progressive policies at the time.

Coleman took French-language classes in Chicago before traveling to Paris to earn her license in November of 1920.

After studying for 10 months, in June of 1921, Coleman became the first Black woman and the first Native American to earn her pilot license. She received her license from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale.

By the time she returned to America later that year, she was already a highly-regarded, famous figure across the country.

Coleman focused her attention on "barnstorming," which is when stunt pilots perform dangerous tricks while flying their planes.

With no one in the states to teach her, Coleman headed back to Europe.

It was around this time she started performing and earned the nickname "Queen Bess" as well as "Brave Bessie."

In September of 1922, Coleman made her first appearance in America at an event honoring veterans of the all-Black 369th Infantry Regiment from World War I.

After touring around both the East and West coasts of the U.S., Coleman returned to Texas to set up her headquarters in Houston in 1925.

During her performances, Coleman often showcased stunts such as figure eights, loops and near-ground dips.

In June of 1925, Coleman put on a show at Houston's Aerial Transport Field, which was her first performance in her home state.

Coleman made sure to regularly speak out against racism at her events, telling audience members about the number of Black people who want and should be encouraged to become pilots.

She refused to be a part of any events that wouldn't allow Black people in the audience. She also wouldn't perform if audience members had to enter the location through separate gates based on their race.

Coleman was given the chance to be in the movie, Shadow and Sunshine.

However, once she learned what the filmmakers wanted her to wear and how she would be stereotypically depicted, she stepped away.

In April of 1926, Coleman planned to fly in Jacksonville, Florida in a plane she recently bought in Dallas.

About 10 minutes into her flight, the plane took a dive, spinning to the ground and crashed, killing Bessie Coleman at the age of 34.

While there was little media coverage at the time, news of her deaths deeply impacted the Black community across the country. Activist Ida B. Wells led ceremonies at her burial site in front of 10,000 people paying their respects.

Soon after her death, aviation clubs and organizations connected to her name started sprouting throughout the nation.

In Atlanta, Texas, where Coleman's life began, there is a section in the city's regional history museum devoted to her story that includes a uniform and memorabilia from her life.

This includes a downscale version of her yellow plane, "Queen Bess."

Outside the local museum in downtown Atlanta, there is also a historical marker.

Roads at multiple airports around the world, including O'Hare International Airport in Chicago, are named in her honor.

Cedar Hill ISD has Bessie Coleman Middle School, which has parts to her story spread throughout the hallways.

Coleman has been inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame, the National Aviation Hall of Fame and the International Air & Space Hall of Fame.

While she countless accolades and awards, what might make Coleman the proudest is the number of aviation groups and clubs filled with a diverse group of pilots that can be thankful Coleman established herself as one of the true pioneers of the air.